This website started as a way to share our early research regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. We were trying to write down for ourselves and our friends what to do when so many people were going to get sick. Much of what’s discussed here may be common sense to some, but we felt it’s still good to have some checklists and information for various stages of illness in one place. We consulted with nurses and doctors, but this site was created by the non-medically trained, trying to puzzle together what makes sense in our new normal.

PLEASE READ THIS

To be clear: LISTEN TO LOCAL HEALTH AUTHORITIES, DOCTORS AND NURSES when given the choice between that and something you found on the internet.

Information on this website is provided for informational purposes only and is not meant to be a substitute for advice provided by a doctor or qualified healthcare professional. Patients should not use the information provided here for diagnosing a health condition, problem or disease. Patients should always consult with a doctor or other healthcare professional for medical advice or information about diagnosis and treatment.

IN EMERGENCIES, DIAL YOUR LOCAL EMERGENCY TELEPHONE NUMBER.

As we started writing for this site in Berlin, Germany in the second week of March 2020, much about the virus was still unclear, but numbers of infected and dead were rising steadily, most recently in Italy. Whether the virus has caused total crisis where you are or not: It is time to think and prepare.

This guide is based on the assumption that in the coming months, more people than usual will either become ill or have ill people in their lives. Let’s all hope for the best, but we’re going to assume that doctors and hospitals are going to be very busy if not overloaded. We have to confront the possibility that some of the people who would normally be cared for under medical supervision might need to be cared for at home. We hope some of the information here will give you some confidence in dealing with this disease, which in and by itself will reduce the load on doctors and nurses who, from the looks of it, will be quite busy in weeks and months to come. At the same time, we hope to give you information that helps you tell when it is time to get professional medical help. Getting large amounts of people to get that balance right may make all the difference in the time to come.

What this guide is not…

We try to provide a large amount of general helpful tips for dealing with COVID-19 during the various stages in which it might affect your household. What we cannot do is provide up-to-date information that is specific to where you are. We will try to tell you when we think you need to seek up-to-date local information in text boxes such as this.

Note that any advice from official sources you may find could be outdated as soon as a few days after it is issued, so always try to find the latest guidance and advice you can. Refer to local broadcast media and trusted information on the internet. Your local health authorities know the situation on the ground where you are, and should be talking to the public through the media.

That said, we are seeing various levels of quality in official response. Sometimes there will insufficient capacity to supply everyone with individual help and advice, for example because hotlines and testing centers are overloaded. Help may well be unavailable at some times. In this text we will just keep going, giving you the best information we found in our research. This doesn’t mean we think such general information as is on this site could be better than local help from trained professionals. Treat the advanced chapters of this website as a last resort: much better than nothing, but by all means get local help from actual professionals if you can.

Also note that we do not sugar-coat. This site is written by and for adults who can handle thinking through the consequences of our current global predicament. There is no reason to panic, but the situation is serious enough that we feel everyone should have access to the best information we could find.

Some of the authors of this website are not known as great fans of government and authority, but at this point trust in the public health authorities is vital. Where there are discrepancies, trust reputable sources such as:

- World Health Organization (International)

- Centers for Disease Control (USA)

- National Health Service (UK)

- Robert Koch Institute (Germany)

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (EU)

- And the public health authorities where you are.

For the more research-minded, we compiled a list of additional resources.

Know the Facts:

- COVID-19 is real.

- It’s a disease caused by the new SARS-CoV-2 virus that mutated to infect human hosts after starting in animals.

- COVID-19 is dangerous.

- The virus that causes it seems to spread far more readily than SARS.

- It seems to commonly cause pneumonia, while most cases of the seasonal influenza virus (flu) do not (and those that do are more dangerous). COVID-19 is also associated with far more other, serious complications requiring medical care, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), cardiac events (especially in people with existing heart disease), respiratory failure, septic shock, liver injury, and multi-organ failure. It seems to cause over 3x and possibly 10x more deaths than the flu. (But until testing is much more widespread, it will be impossible to know for sure.)

- Unlike the flu and other diseases, there are currently no known vaccines or anti-viral treatments for COVID-19 supported by sufficient scientific evidence from double-blind, randomized controlled trials. (Though you can be sure research is ongoing worldwide!)

- It’s also worse than the flu because the world population so far lacks immunity. New pathogens are more potentially dangerous, because their infection rates can grow incredibly rapidly (even having ). Such rapid transmission of a new pathogen that commonly causes disease severe enough to require medical care can swiftly overwhelm even the world’s best healthcare systems, making it impossible for everyone who needs care (including for unrelated conditions) to access it – and in turn contributing to even more severe disease and more, otherwise avoidable deaths.

- Slowing the spread of COVID-19 down (also known as mitigation) is the best chance we still have to save a large number of lives. Slowing the spread down requires widespread cooperation with and implementation of measures like reporting your symptoms to the authorities where required, accessible testing, isolation of the sick and those exposed to them, and social distancing – sometimes even rising to the level of mandatory sheltering in place – for everyone else (see Level 1 below).

- For these reasons, many have changed or will soon need to change their way of life to address the very real threat this pandemic poses to everyone on Planet Earth.

Remember that there is no difference in potential infectiousness between friends and strangers. There is no race, ethnic group, or nationality that is innately more likely to get or transmit the virus than another. Try to help others when you can without being in physical contact with other people unnecessarily: A lot will depend on whether the social fabric of our society holds. Slowing the spread of an infectious disease is rarely absolute. But taken over society as a whole, our efforts still work when everyone does what they can, within their limits.

You can help make this site better

If you see something that could be better, please click here to file an issue. We promise to do our best to respond quickly. (As you can see there, the back end of this website is on Github, so if you know that environment you can also send pull-requests or think of other ways to help.)

To be successful, this will need to be an expanding, collaborative effort.

Level 1 – Healthy

Don’t Get Infected - And Don’t Infect Others

You might feel fine. But the virus can spread before you show symptoms. Some people can spread it without ever showing symptoms. Some people might have more severe disease after more significant exposures due to increased initial viral load, so it’s worth preventing more exposures even if you think you were already exposed. Overall, follow the instructions from authorities. This includes some of the by-now familiar guidelines for social distancing:

Stay home

- Work and study from home when possible.

- Use alternatives to in-person meetings (e.g., video or voice calls) when possible.

- Avoid crowds and unnecessary travel. If you must go shopping, do it when stores are less likely to be busy. If you must be in a crowd, try to keep your safe distance of at least 1.5 meters (or around five feet) from others. Move away from anyone who seems to be ill (e.g., is coughing or appears feverish).

Use appropriate hygiene

- Change your greetings. Instead of a handshake, hug, or kiss(es), try waving or bowing from a distance, namaskar 🙏 or bumping elbows or feet.

- Your eyes, nose, and mouth are possible places for the virus to enter your body. So wash your hands before touching your face. Don’t touch your face while outside.

- Take care with handwashing hygiene.

- Wash your hands thoroughly for 20 seconds with soap and water as soon as you come home, before preparing food or eating, and after using the toilet.

- Use soap and water, not hand sanitizer, when possible: It is more reliable because you can easily cover every wrinkly bit of skin on your entire hand with enough soapy water to get rid of the virus.

- Watch a video or two on just to be sure you are using it.

- Use moisturizer as needed, too: Keeping skin healthy makes disinfection more effective and reduces the risk of infection from other germs, because dry and damaged skin is more vulnerable to infection.

- Regularly clean doorknobs, light switches, table surfaces, keyboards, cell phones, and other things people frequently touch. If the items or surfaces are dirty, first clean them with soapy water, removing any visible dirt. Then, apply disinfectant (e.g., your favorite household cleaner, diluted bleach or hydrogen peroxide solution). If surfaces are already clean, just apply disinfectant. If you are not ill and no one around you has been ill, weekly cleaning is fine. Otherwise, clean high-touch surfaces daily if possible.

- Cough and sneeze into your elbow, not into your hand or unprotected.

Take care around food

- Instead of going to restaurants, cook and eat at home.

- Instead of having food or groceries delivered or delivering them to another person at home with direct contact, arrange to have them left or to leave them outside the door.

- Instead of meeting friends for lunch or coffee, have a video-chat or coordinate a walk to the grocery store while keeping your safe distance.

Take care going outside

- when you go outside. Make your own using our mask-making template if you cannot find one for purchase. You may also wish to wear disposable gloves, for instance, while buying food or medicines in shops where you will need to touch surfaces many other people may have touched. For more information on personal protective equipment such as this, see this list.

- Wash your hands and change your clothes when you get home. If you’ve been around someone who seemed ill, wash them at 60° Celsius (140° Fahrenheit).

- Instead of taking public transportation, walk or bike wherever you can. If you must take public transport, again, keep your safe distance from others and move away from anyone who is ill.

- Instead of exercising inside, go outside for a walk or run in your neighborhood if weather permits, while keeping your safe distance from other people.

Here you will need up-to-date local information. Walks outside may well be illegal where you are (for a time), while much of this advice may actually be mandatory. You may be asked or required to do other things not on this list, like having your temperature taken before buying groceries. Let up-to-date, local information guide you where there are conflicts between that and this text.

Stay Healthy

On top of this, you can do things to stay as healthy as possible:

- Improve your air quality. Avoid second-hand smoke, mold, and other sources of indoor air pollution, which weakens your lungs and increases your vulnerability to infection. Ventilate your rooms frequently, including especially while cooking.

- Eat well. Avoid ultra-processed foods. Prefer nutrient-rich whole foods (like fruits and vegetables, nuts, legumes, dairy, eggs, meat) with no additives, the fresher the better. Choose whole grain over refined and complex over simple carbohydrates; opt for lower glycemic index alternatives whenever possible. Vitamins D (“the sunshine vitamin”) and C can be especially helpful in preventing or mitigating the effects of respiratory infections.

- Drink enough, mostly water. Your urine should be very light-colored, never dark yellow.

- Get regular exercise. If it is recommended or required to stay indoors, find ways to get moving at home: Dance to favorite songs with friends over video-chat, join online yoga or other exercise classes, or try simple core bodyweight exercises like push-ups, sit-ups, and squats combined with simple stationary aerobic exercises like jumping jacks, hula hooping, and skipping.

- If you smoke, stop smoking! For the longer version of that, read this article which says:

An article reporting disease outcomes in 1,099 laboratory confirmed cases of covid-19 reported that 12.4% (17/137) of current smokers died, required intensive care unit admission or mechanical ventilation compared with 4.7% (44/927) among never smokers. Smoking prevalence among men in China is approximately 48% but only 3% in women; this is coupled with findings from the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019, which reports a higher case fatality rate among males compared with females (4.7% vs. 2.8%).

- Avoid heavy drinking and other drug use, as alcohol and other drugs tend to suppress immune function.

- Avoid soft drinks and other high-sugar, ultra-processed, low-nutrient food and drink, as these tend to contribute to inflammation.

- If you want to do more after first covering these essentials, then consider complementary medicine options to improve immunity, prevent and treat upper respiratory and / or viral infections, and the like. There are a number of possibly useful options – but keep in mind that the evidence so far is specific to different (though related) contexts, because this is a new disease. A lot of snake-oil salesmen are going to make a lot of money off of panic here without offering actual help. Don’t fall for them.

Psychological well-being

This is going to be rough on all of us at times, and it is going to affect each and every one of us differently. Isolation in general can make every possible sort of mental health problem worse. Furthermore, this is a situation where it’s completely normal to worry about being or getting sick. Having COVID-19 can also be quite psychologically stressful for some. And then there are special stressors that many will experience, such as the psychological toll of the trauma of an outbreak like this on most healthcare workers, particularly emergency department professionals. Here are a few recommendations and tips for psychological well-being in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, taken mainly from the Austrian Federal Ministry of Defense (go figure!), summarized and expanded on briefly below. None of this will be right for everyone, but (hopefully) you know you well enough to find what is right for you:

- Remember your choices help others. Every time you take more care to avoid getting sick or spreading the virus, you are helping others. This is true even if you feel well, since you could be asymptomatic and still infect other people – someone else’s mother, father, sister, brother, daughter, son. So celebrate your everyday choices that help other people. That empowerment and altruism may benefit your own mental health.

- Stay informed. Getting regular information from reputable sources establishes a sense of security. Maybe you want to combine these first two hints by finding a way to help combat misinformation, which is a serious part of the public health challenge of the current pandemic. For example, when you see or hear someone you know spreading rumors or falsehoods, suggest reputable sources in a way that lets them know you care (and don’t just want to be right). What we know about this new disease is changing so quickly, everyone needs a little help sometimes keeping current.

- Feelings are fine. It’s normal to experience many emotions – sometimes in quick succession – in crisis situations. Accept what you experience without judgment and wait to make major decisions.

- Focus forward. What do you want to accomplish in this strange window of opportunity? It could be something as simple as writing a diary to express how you are feeling, watching a favorite show on Youtube in a foreign language you want to learn, or reorganizing your kitchen cabinets. Start small and just do something.

- Communicate. Stay in touch with people near and dear to you. You might consider setting aside part of the conversation to talk about the current crisis and your worries – and part of it to talk about other things. Watch and listen to know when you or others are becoming overwhelmed. It’s ok to refocus on brighter spots – what are you enjoying doing lately? What are you excited about doing someday? Cooking, art and crafts, music, reading, watching movies, and writing are examples of sometimes solitary pursuits that might bring you joy.

- Laugh, dammit. Look up your favorite comedians on Youtube or go hunting for new ones. Film a song parody or silly sketch for your friends. Think about your favorite comics as a kid, and see if you can get your hands on a comic book or anthology.

- Move. Whether aerobic or non-aerobic (or both), do some form of exercise that you can enjoy. It’s not only good for your physical health, but also for your psychological well-being.

- Find your routine. Having regular times or orders in which you do things (eat, work, play, sleep) helps some people stay on an even keel.

- Be your own friend (coach, cheerleader). Fear and other negatives are easier to notice and remember than love and other positives – our brains had to evolve this way to help us be alert to predators and survive in different environments than we now find ourselves (like the open savannah). Help your brain adapt to living in the modern world instead by reorienting your attention toward the good things going on. Look for evidence that people are being kind to others. Have faith that you and your dear ones will be able to cope with the situation together. Imagine your future self achieving the best you can, and celebrate that you have had the strength to get through this.

- Talk to your kids. Ask what they know and what they want to know, provide structure and routine, stay calm, and play together.

Prepare

And on top of that, you can prepare so that you are familiar with the things that you will need to do when disease comes knocking. Read the rest of this guide. It is statistically unlikely anyone in your household will develop life-threatening complications, and hopefully there will be plenty of medical care for everyone. But in these times it doesn’t hurt to be a tiny bit more ready for the worst-case scenario.

Remember, at the same time, that there is no reason to panic. Take a deep breath and continue your regular life as much as possible.

Get the things you need

We made a shopping page that lists handy things that may help you care for yourself and others.

Reach out

If you live alone, now is a good time to think who you can ask to check on you regularly if you become ill. If someone you know and love lives alone, now is a good time to be in touch to see how they are doing.

Existing Medical Conditions

If you or your loved ones have existing medical conditions, now is the time to read up on how these conditions could be made worse by COVID-19 / pneumonia. Reputable sources for health information about a wide variety of conditions include the National Institutes of Health, the NHS, and Mayo Clinic. You / they should also make extra sure that you / they have plenty of all of your / their necessary medications. Make sure you have all the information relevant for treatment (contact info of doctors, recent lab results, how much of which drugs the patient is taking). Assume for a moment that your regular doctor isn’t there and you have to explain it all to a new doctor who has very little time. A recent timeline of visits, results, etc. would be nice. What should you not forget? Write it down now!

What sorts of existing medical conditions are especially likely to make you / your loved ones vulnerable to more severe COVID-19 problems?

- Conditions that involve lungs / breathing problems (e.g., asthma, COPD, lung cancer).

- Heart conditions, particularly chronic cardiovascular disease (e.g., hypertension, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation).

- Conditions that involve compromised immune function and / or require taking immunosuppressant medications (e.g., lupus, arthritis, organ transplantation, some cancers).

- Other chronic hematologic, hepatic, metabolic, neurologic, neuromuscular, or renal disorders (e.g., sickle cell anemia, diabetes, muscular dystrophy, kidney disease).

Preventive Care

If the news is full of stories of hospitals being overloaded with COVID-19 patients where you are, then ignore the text below and let the doctors and nurses work. Except when local health authorities tell you otherwise, naturally.

If the situation is still somewhat normal where you are, this may be good moment to briefly ask your doctor what (if anything) she/he thinks you should do now, and what you should do if you fall ill. If you have not yet been vaccinated for the seasonal flu, pneumococcal pneumonia, or meningococcal meningitis, now may also be a good time to ask your doctor if you are a candidate for those vaccines. Getting these vaccinations now if your doctor advises it could help prevent another infection from compounding problems that may be caused by COVID-19, should you be infected later.

During pandemics, it is typical for childhood immunizations, maternal healthcare, and healthcare for chronic health conditions to get cancelled or delayed because doctors, nurses, hospitals, and the rest of the healthcare system may be overloaded, and because people may be afraid to go in to doctors’ offices or hospitals for fear (sometimes rational) of being exposed to disease. In case your area is not yet greatly affected by COVID-19: Is there any normal childhood vaccination you want to be sure your child gets while he or she can? Any prenatal care or routine care for a chronic health condition you can get now instead of in a month? What about other conditions that are common ailments for you or your loved ones? Anything you can do to prepare to care for yourselves without normal medical care access in the coming months, in case it becomes harder to get time with doctors and nurses because they are overwhelmed? Do it now.

That said, it is never time to delay needed, urgent medical care. Not even during a pandemic. If you develop symptoms for which you would normally seek urgent medical care, then please find a way to seek that care promptly even if the normal avenues are closed or you are afraid of being exposed to the virus in a healthcare setting. This is especially true if you develop signs of a stroke. Those signs are easy to remember with the acronym FAST: Facial drooping, Arm weakness, Speech difficulty, and Time, as in, it’s time to get help. Sudden strokes of a dangerous kind appear to be much more common in otherwise healthy, young adults due to COVID-19, including in people who are only mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic but positive for COVID-19. Prompt stroke care is essential to prevent more permanent damage. This is a case where getting needed care as soon as possible is a form of preventive care, too.

Life, death, dignity, and choices

Let’s be straight: COVID-19 is potentially lethal, and this is even more true if you are middle-aged or older (because there is a strong age gradient in risk of death from it) and / or have existing medical problems (especially ones affecting the lungs, heart, or immune function). We hate to bring up some potentially depressing things right here in Level 1, when you and your loved ones are not even infected with the virus. But, if at all possible, you want to be level-headed and not rushed when you think about these things.

First, remember not to panic. Of all the people who get infected with the virus, many will show no symptoms. The majority of people who do show symptoms will have a mild or moderate version of the disease. The majority of the people who get sick do not need to go to hospital. Even among risk groups such as the elderly and people with multiple existing medical problems, most will survive. That all being said: the sad reality is that some COVID-19 patients will develop severe respiratory problems, and of those, some will die.

Many people have previously thought about how they would like to die when the time comes. We know most people (ourselves included) hate to think about death, but here are a few things that may guide your thinking:

- There’s no point in not mentioning it, since it’s all over the news: The COVID-19 crisis is already forcing doctors in the most affected areas to make terrible choices to distribute limited resources to the patients with the best prospects for recovery. For patients who are older (and this may mean different ages at different places and times) and / or have existing health problems, the terrible truth is that during the peak in cases in your area, some may simply not qualify for treatment.

- When thinking about the above, it’s important to simultaneously realize than even in the best of times, elderly people (generally defined as 65 years or older) with existing conditions have a low survival rate once they need to be mechanically ventilated.

- You may or may not want to be explicit as to what you want in case you face difficulty breathing. Many countries have “living will” (also known as advance directive) documents that let patients tell doctors what treatments they would not like to receive. Talk to your doctor if still possible and openly discuss different scenarios.

- Death in a hospital is likely to be a heartbreakingly lonely and technical affair that may first involve intubation, all sorts of other tubes and machines – and isolation from home and loved ones, possibly even during the last moments. Many hospitals have already stopped visitation altogether in order to lessen the spread of COVID-19.

- On the other hand, if you decide to stay at home when the time comes, you may need to arrange for palliative care and possibly for spiritual/religious and emotional support to the extent desired and possible. You may also want to pre-arrange access to pallative care medication (such as opiates and sedatives) that is no longer intended to prolong life, but to ease suffering during the dying process. In some countries, doctors can help patients have such medicines at home before the situation is dire, in case the time comes.

- You may want to talk about these things with others close to you if you find these issues difficult to think about on your own.

Level 2 – Emerging Symptoms

Notice if you suffer anew from any of the following, most common first COVID-19 symptoms:

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Dry (unproductive), persistent cough

- Shortness of breath

- Gastrointestinal symptoms

Fever seems to be the most common symptom – but it’s not universal. Early data showed that gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, loss of appetite) were uncommon. But more recent evidence suggests that they are common, and can even precede respiratory symptoms. Initial symptoms may also include joint / muscle pain, headache, chills, dizziness, nasal congestion, and sore throat. Loss of smell and taste lasting for several days can start early or later in the infection. So can skin symptoms like a rash on the back, chest, or stomach (in about 20% of cases in one sample), or small red or purple-colored lesions around the tip of the toes (especially in children and adolescents).

However, common colds, flu, and allergies can also cause many of the same symptoms. In fact, nasal congestion, itchy eyes, and sneezing most likely indicate a condition other than COVID-19, such as allergies. There is no single, unique COVID-19 sign or symptom. There is no way to know for sure whether you have COVID-19 without testing for it.

Is COVID-19 spread in the community where you live? Or have you been to an affected area or been around someone who was in an affected area? Then your symptoms could very well be COVID-19. But remember: In many areas, the odds that it’s something else will still be greater.

Note: Fever is not subjective. You will need a thermometer (or two, in case one breaks), and to keep track in a log of at least daily temperature. If you choose to take temperature internally (i.e., in the bottom / rectum), it will be more precise. Be sure you have enough wipes and alcohol to clean the thermometer after each use. If taking temperature orally, don’t eat or drink for 20 minutes beforehand. Either way, note the method in your illness diary (more on this below), so that healthcare personnel know which it is. (Around .7° Celsius or 1° Farenheit is often added to oral temperatures.) Here are some good instructions for how to take an oral temperature.

If you don’t have symptoms

Some people may be exposed to, carry, and infect others with the virus – without ever showing symptoms themselves. These people are asymptomatic carriers. They seem to be common; they may even number around one in four of those infected. Unless widespread testing is available where you are (which is currently a small minority of places), it may not be possible to determine if you are one of them. This is one of the reasons why everyone should currently be following the advice of public health authorities that generally includes social distancing measures covered in Level 1.

If you have symptoms

The single most important thing once you have symptoms that might be COVID-19 is to stay at home, or to go home if you discover them while not at home. Call in sick. Stay away from people as much as possible and go to a separate room if you live with others. If you live alone, let someone (friend, family) know that you are ill and will keep letting them know how you’re doing.

Symptoms? Maybe you need to register…

As this point you need up-to-date local information. Your health authorities may want to know if you have symptoms. Reasons for this may include population monitoring to see where the virus is, planning the government’s response as well as opening a channel to follow up with you personally. There may be a phone number to call if you have symptoms, or a website to visit, or an app to download. Just figure out what the authorities in your area want you to do as soon as you have isolated yourself from others.

Diagnosis

You will want to know whether what you have is just a cold, a flu or actual COVID-19. There will be different policies surrounding testing for COVID-19 based on where you are and what stage of the pandemic your area is in. Check online, call official hotline numbers, follow official guidelines. If testing capacity is limited, you may not qualify for testing, even if you have all the symptoms of COVID-19.

You may find that the official information on getting tested doesn’t always match the reality on the ground. It may be impossible to get through, the lines may be way too long, the waiting conditions may be unsafe. (You don’t want to get COVID-19 from trying to find out if you have it.)

In some cities, your regular doctor will come to your home in full gear to swab your throat. In other places, there are drive-throughs. There are also Do-It-Yourself test kits you can order by mail where you perform your own throat swab and send it to the lab for testing. The availability of all of these methods will differ depending on where you are, who you are, what stage the pandemic is in and many other factors. We cannot possibly help you further than to tell you to inform yourself as soon as you have isolated yourself.

Under no circumstances should you just show up at a doctor’s office or a hospital unannounced if you experience symptoms.

Remember: This is for your own protection as well as that of the other patients. Hospitals are bad places to be until you absolutely have to be there: You run the risk of getting additional infections that, when bacterial or fungal, are much more likely to be resistant to standard treatments due to the nature of the hospital environment. Also: Many hospitals are going to be overloaded, so waiting times may be astronomical.

Don’t Panic

For most people, this will be as bad as it gets. You’ll be a little sick, and then you’ll get better. Done.

At the same time, some people will not be so lucky. Even if only a relatively small percentage of those affected need medical care, this will put a serious strain on doctors, nurses, and available medical resources. We can all help them by staying home whenever possible.

The “Worried Well” is a medical term for people who visit the doctor when they are not really (all that) sick, because they need reassurance. The coming weeks and months are not a good time for that. This website aims to give you more confidence and preparedness in caring for yourself, friends, and loved ones until you / they actually need professional help.

Consider using relaxation techniques to slow a rapid breath or heart rate that may be partially due to anxiety (or just to chill out):

- Listen to calming music.

- Check in with a friend electronically.

- See if you can slow your breathing and bring down your heart rate by counting longer for forceful exhaling than for gentle inhaling. Some people use 4-7-8, and others prefer 5-2-5 to try slowing down their inhale-hold-exhale patterns. Use what feels best for you.

Self-quarantine

Until tested and depending on where you are and where you have been, simply assume the patient (you? a family member?) has COVID-19. That means self-quarantine at home. No more visitors, a sign on the door, and the patient should not go out unless there is no chance of meeting anyone. Different areas have different standards for what it means to self-quarantine when there are other people in the household. If possible, you will want to err on the side of safety and try to get everything delivered for 2 weeks. Things may change, as in some areas the virus will become so common (endemic) that many people will have had it. There is no telling at what point various authorities will stop testing every potential infection, and it will differ from region to region.

Garbage

During this time at least, err on the side of caution when it comes to trash. Used tissues, paper towels, and other possibly contaminated disposable items should be bagged in disposable trash bags, tied securely, and put aside for 72 hours prior to external disposal. Some places also recommend putting these items in a second disposable trash bag. If you use communal garbage bins, disinfect the handles when possible before and after use. Wash your hands after handling trash and bins.

PPE

Now at the latest is time to think about Personal Protection Equipment (PPE). If you can get masks AND IF MASKS ARE NOT IN SHORT SUPPLY FOR DOCTORS AND NURSES WHERE YOU ARE, wear one outdoors. You are not supposed to be outdoors when you have symptoms, we know. But we mean even just when taking out the trash. If you have no mask, at least do something. Make your own using our mask-making template. Wrap a towel around your nose and mouth, breathe through a scarf, anything is better than nothing. Here are a few recommendations for PPE in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, summarized and expanded on briefly below:

- Use PPE if you are sick and have to be around other people, or if you feel well but have to be around someone who is sick (e.g., caring for someone).

- Use a high-filtration respirator like an N95, FFP2, or FFP3 if you can. Next-preferred would be a regular medical face mask (surgical or procedural). Then a home-made or improvised mask. Just use something.

- Use disposable gloves to take out the trash when you are ill, or when caring for someone who is ill.

- It may make sense to also use a cap, gown, and eye protection if you are caring for someone with COVID-19 at home.

- Fitting respirators properly is hard and important; look up and mold it to your face with your fingers without squeezing the bridge.

- Take care putting it on. Start in a clean zone with clean hands and keep your PPE as clean as possible.

- Take care taking it off. First remove gloves and wash hands, then remove mask and wash hands, then remove any other PPE or dirty clothes and wash hands. Then put on clean clothes and get back to a clean zone.

- Dispose of used gloves in a disposable trash bag, double-bagging and / or placing the trash aside for 72 hours before external disposal.

- Although this is not normal, you probably want to reuse masks since they are already in short supply globally (and the same may become true for other PPE). The best way to reuse PPE is to mark seven sets – one for each day of the week. Rotate them after wearing to sit in a clean place for a week. If you need respirators / masks decontaminated faster, bake them in the oven at 70° Celsius (around 160° Farenheit) for 30 minutes.

Family, flatmates, etc.

Seek up-to-date local information if you live with others. The authorities may provide you with different or more detailed instructions, advice, or even PPE materials.

Here are some general suggestions and tips for dealing with family and flatmates if you have or suspect you may have COVID-19:

- Self-quarantine from the outside… Household members of people who are known or suspected to be infected should treat themselves as potentially also infected and self-quarantine, too.

- … and distance on the inside. They should also keep the maximum practicable distance from the patient for as long as the patient can take care of him- or herself. This means being in different rooms, sleeping in different beds, eating separately, using different dishes and towels, and when possible, using different bathrooms. (If that’s not possible, at least keep contaminated toilettries like the patient’s toothbruh in a separate space such as the patient’s room for now.) We know, distancing in your own home and possibly from your own family, is weird and sometimes heartbreakingly hard. But this is a potentially lethal disease and the people close to you will (hopefully) understand.

- Clean the kitchen faucet. Regularly clean all frequently touched surfaces (doorknobs, light switches, table surfaces, keyboards, phones, toilet handles if in shared bathrooms, kitchen faucet handles if in shared kitchens – you get the idea) with a regular household cleaner (e.g., Lysol, Windex), hydrogen peroxide solution, or diluted bleach (10 ml / 2 tsp bleach with half a liter / 2 cups of water; carefully washing measurement tools before reuse). You can put that solution in a disused plant sprayer or cleaner spray bottle. Give the cleaner a minute to work on surfaces before wiping it dry.

- Consider PPE. Your housemates might want to wear masks indoors, too. When they handle your trash or laundry, disposable gloves are also a good idea.

In most places, there will probably come a time when the number of cases skyrockets, many people have already had COVID-19, and authorities will no longer keep records of who has had it and who hasn’t. The basics then remain the same: Try to protect other people, especially those middle-aged or older and people with existing illnesses, as much as possible. And try to minimize the spread whenever you can, as best you can. Remember: The more we can slow or stop the disease’s spread, the better it is for everyone. Because by helping to slow or stop the spread, you help lessen how overwhelmed the healthcare system is going to become. That in turn increases the proportion and number of people who need medical care (for any reason), who are able to access it. This helps doctors and nurses save more lives.

Diary

When symptoms first start is the right time to start an illness diary.

A few times a day, preferably at somewhat regular hours or points in your normal routines or rhythms (e.g., every morning before making coffee or tea), measure temperature, even if you don’t feel like you have a fever (yet). Weigh once a day if possible. Also note respiratory and heart rates in breaths and beats per minute. It will get you used to doing these things, give you practise, and (if you start early) give you some idea what (more or less) healthy values for you look like. Not necessary, but extra points for blood pressure and oxygenation (Devices to measure those are cheap, see the shopping page).

Then write down any symptoms the patient has. If he or she is in pain, where and when is the pain, and how bad on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable)? How bad is the cough? What color if there is mucus being produced? Be sure to note what medication, if any, the patient takes.

Paracetamol (also known as Tylenol or acetaminophen) is a good choice for fever and pain suppression. Keeping an illness diary will also help you to keep track of how much you’ve taken, when, to ensure you treat fever adequately without taking more than the recommended amount in a 24-hour period.

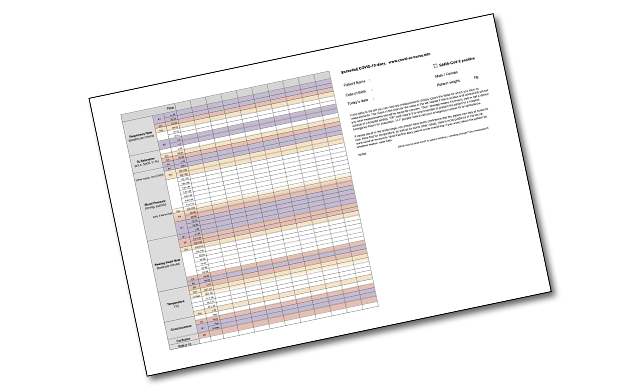

Printable illness diary

We made a printable illness diary that you can use to write down all the information you collect when you take temperature, breathing rate, etc. Please check out the form and our webpage about it via the link above.

Contact lenses

Even when you are not that ill yet, it is much better to use glasses if you have them, and stop routinely putting in contact lenses in the morning. You do not want to touch your eyes more than you have to because they may get infected. If and when you do get more ill, you do not want to risk forgetting that you have them in.

Get healthy again

-

Rest as much as you need to. Tiredness is a common symptom. Let your body use its energy to fight for health. Do the bare minimum of everything else.

- Treat fever with care.

- Treat pain and fever with over-the-counter medication at the recommended safe dosages. Use paracetamol if you can.

- Fever is part of the body’s natural defenses. Research suggests medicating fever less rather than more aggressively is safer. This means medicating a temperature of over 40° Celsius (104° Farenheit) – and not medicating a lower fever.

- Questions are also emerging surrounding the safety of ibuprofen / non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), as well as corticosteroids / steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, in case of coronavirus. If possible, avoid their use if you have symptoms.

- An additional safe way to treat fever is to take a bath or shower. The water temperature should be comfortable, not cold, because shivering can raise your core body temperature – and the idea is to lower it. When you get out of the bath or shower, the leftover water evaporating from your skin can help lower your temperature.

-

Keep eating. Try to keep eating nutritious food. Nothing too heavy, not too much at the same time. Lots of vitamin-rich, unprocessed food like fresh vegetables and fruit. If you’re not eating, maybe drink one of those big multi-vitamin pills that fizz into water.

-

Steam. Inhale steam daily. The best way to do this is with a steam inhaler, a device that outputs steam that is not too hot to breathe. A humidifier or shower also works. The older method many people know is to boil water in a pot and then put your head over it, under a dishtowel; just make sure you don’t do damage with hot water or steam that’s too hot to breathe. There are no miracle cures and this is no exception; it just helps your airways open and drain a bit better.

-

Keep moving. Go for a daily walk in the fresh air and sunlight when possible, while keeping your safe distance from other people. Exceptions: You’re too tired – then rest! You’re symptomatic and can’t get out of your apartment building without coughing in the shared elevator – stay home!

- Keep drinking.

- This is really key. Drinking enough fluids helps the lungs produce secretions, and helps those secretions it does produce be thin enough to potentially cough up.

- If your throat is irritated, avoid acidic drinks (such as soda and juice) as they can be further irritating; water and teas are better choices then.

- How much is enough? Notice the color and amount of your urine. If it is dark (more colored than clear), or there is not a lot, drink more water.

- It is very important to avoid and treat dehydration by drinking enough, even though it can be hard to drink enough when you have a fever / are sweating a lot, and are suffering from fatigue and discomfort due to illness. If you are struggling to drink enough and beginning to show signs of dehydration like darker urine, you might also try eating foods containing more water (e.g., cucumber, oranges, apples), sipping on boullion or soup, or setting a small goal for yourself (e.g., every time you get up, drink a glass of water).

- Encourage coughing.

- Coughing can be an important, healthy effort on the part of the body to clear the lungs of fluid so you can breathe easier. It’s also exercise for your lungs.

- Do not suppress a productive cough all the time / just because you don’t want to be coughing. However, if you want to try to suppress your cough enough to get a good night’s sleep so your body can better heal itself, then over-the-counter cough medications, herbal teas such as anise / chamomile, cocoa, and lozenges can help.

- Some over-the-counter cough medications contain ingredients like guaifenesin or NAC, generally considered safe mucolytics that relieve coughing by helping your body get rid of mucus (usually by making it thinner and so easier to cough up); your pharmacist can help you find one that’s right for you.

- Get up, stand up. Other simple ways to try to prevent pneumonia and other lung complications from developing typically include:

- Sitting upright as much as possible to help fluids drain. Do not lie flat in bed all day.

- Getting up and moving periodically. Although you may be very tired (malaise) due to your illness, being upright and moving around can similarly help fluids drain.

- Expanding your lungs by breathing deeply (in and out), and raising your arms (up above your head and down again).

- Opening the window and breathing the fresh air, especially if breathlessness is bothering you.

- Exercising your fuller lung capacity by blowing up a balloon every hour, using a peashooter, or using any other toy you might have on hand that exercises lung capacity. This is a particularly good idea if your breathing is fast and / or you are feeling breathless. Be gentle and patient with yourself. Focus on taking slow, deep breaths all the way in and all the way out, and remember lung capacity is like muscle strength: You can build it up by repeated exercise. Do 10 deep breaths every hour you’re awake.

Feeling better?

If your symptoms go away, that doesn’t mean you should end your quarantine immediately. You need up-to-date local information again to see whether the authorities want you to register as healed, especially if you tested positive earlier. Depending on availability and local policy, you may need to be tested again. Your local health authorities may provide you with specific advice on what to do next. If so: Follow it.

Absent of up-to-date local instructions from authorities, you should err on the side of safety and try to stay in isolation for a little longer than officially indicated. The World Health Organization recommendation is to continue isolation for at least two weeks after symptoms disappear, even if you are no longer feeling sick.

If you managed to get tested, yay! You now know that your body (presumably, keep watching the latest science on this) has built immunity. Which means that this thing is over for you, and, if you are young and healthy, also that you are a more logical choice to help your family and friends when they get sick. Depending on what state the world is in, you may want to inform your employer and others who might depend on you that you’ve had it, so they know you’re immune.

Level 3 – Bedridden

All the good care in Level 2 has not worked and things are getting worse. Doesn’t mean you did anything wrong, just keep going. Except you’re getting weaker, and you’re not just coughing anymore, but you feel like absolute crap (doctors call that “general malaise”), things hurt, and you want to be in bed most of the time. It’s easy to forget to eat and drink.

Now that you are really getting ill, it’s time to let your regular General Practitioner / doctor / primary care physician know if you haven’t spoken to him/her already earlier. The doctor may do house visits or have a protocol to assess you over the phone or via videochat. There may be additional advice or guidelines your doctor will give you. Doctors know their patients and can tailor advice to the case at hand. So follow any advice, also if it contradicts any of the more general information given here.

Ask the doctor or otherwise try to use reliable local information to see what, if anything, is expected of people with worsening symptoms where you are. The health authorities may have a website, app, or other mechanism to register a worsening of symptoms. This could be important for keeping an eye on the pandemic, but also to figure out who needs additional care.

If you have no primary care doctor, you will need to seek up-to-date local information on what help is available to you. If all lines everywhere are busy – which is certainly a possibility during the peaks of this crisis – do not panic, just keep trying.

Now that you are sick

- Rest. At this point, rest is very important. Sleep as much as possible. At least in the beginning, you will still be able to get out of bed for limited amounts of time. Toilet, a quick rinse-off shower, weighing once a day (note in diary). Put new sheets on the bed when you can, and make sure the old sheets are washed at 60° Celsius (140° Farenheit) or warmer.

- Get fresh air. Ventilate the room as often as possible.

- Drink more water! More than 2 liters and less then 5 liters a day, or at least 8.5 cups. Remember your body needs more fluids than usual when you’re sweating from a fever. If you have a chronic condition that could worsen with excess fluids (e.g., heart failure or chronic kidney disease), consult a doctor.

- Eat something. Try to eat vitamin-rich foods, but multi-vitamin drink is also ok.

- Use those lungs. See Level 2 on breathing deeply in and out, moving your arms above your head to help your chest fully expand, and even exercising your lung capacity if possible by blowing up a balloon or using another toy that requires blowing every hour.

A typical day

At this stage, a typical day might look something like this:

You get up, weigh, and note weight in illness diary. You might also want to take your temperature first thing, before eating or drinking, especially if you are taking temperature orally – and note it in the illness diary, too.

Then, start drinking fluids. Not too much caffeine or sugar. As much water and herbal tea as you like. Remember you want to drink at least 2 liters (around 8.5 cups) and up to 5 liters a day.

Air out your home as much as possible, perhaps while the water for your morning tea or coffee is boiling. If you have the energy (and enough sheets), consider changing your bed linens if they got sweaty / otherwise soiled. Next, have a quick shower if you’re able. Staying clean can help you feel better mentally and emotionally, as well as physically.

Eat a small, nutritious meal (piece of fresh fruit? handful of salted nuts?) – something that sounds good to you. This is also a good time to take paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) for fever / pain if you really need it, and note the dose and time in your illness diary.

If that was already enough exertion, take a rest. Nap whenever you can – sleep is crucial for healing. If you’re not sleepy but need to rest, then try to rest sitting up to give your lungs a better chance to drain. If you’re still upright, now is a good time to steam to help your sinuses / airways open and mucus to drain.

Speaking of being upright, remember to ventilate your room and breathe in the fresh air. Lift your arms over your head to fully expand your lungs on the inhale. Try blowing up a balloon to fully exhale.

Keep drinking throughout the day. Some people find it helpful to empty and refill a liter bottle of water or a teapot that holds approximately a liter, so that it’s easier to keep track of roughly how much you have drunk. This also makes it easier to keep water by the sofa or bed while you are resting.

Throughout the day, check in with yourself about fatigue (sleep as much as possible), hunger (eat small, nutritious meals), thirst (drink whenever you feel like it), and temperature (take care to keep warm enough). If you feel up to it, and only if you feel up to it, move your body (e.g., go for a short walk as long as it’s still permitted where you are, or get up and dance to a favorite song).

Finally, you want to be alert to signs that your condition may be worsening and you may need more care. So after taking basic care of yourself, then check in with other people around you who know that you are really ill. Let them know how you are doing – and if you need help, ask. Especially let someone know if you start experiencing more severe symptoms (see the next section).

The fork in the road

Current guidance in many places is that COVID-19 patients who cannot take care of themselves (anymore) are treated elsewhere. Given that the patient’s condition can worsen quickly, there are good reasons to be cared for by medically trained professionals who can keep an eye on you – while (hopefully) having adequate protection and training to not get infected themselves. Letting the experts do it instead of staying home also protects your loved ones from infection.

We are seeing this break down in places where there are a lot of cases, with some very ill patients deemed “not sick enough” to go to the hospital, and no other sorts of centralized quarantine facilities with medical staff (yet?) available. This text will continue assuming the COVID-19 patient needs to be cared for at home. This is not the optimal situation. If possible, you should consult with a doctor when you feel you need help before risking anyone becoming infected while they take care of you.

Tell other people around you that you are really ill and are mostly in bed. Talk to someone you trust about how they may have to take care of you. Have this person or these people read this document. If you have people in your environment who have already had COVID-19 (something that will be increasingly common as time goes on), such people would naturally make the best caregivers as they presumably will be (at least partially) COVID-19-immune. Otherwise try to judge what is wisest in your circumstances. By all means do not wait with this until the very last moment, because if the disease progresses, you will get short of breath – which inevitably will also affect your ability to talk and think clearly. Everyone at this level, especially patients who live alone, should really have someone checking on them regularly, because the deterioration in respiratory function can be very fast, especially in the second week.

Others taking care of you

If non-medical people are going to need to take care of you (or if you need to take care of someone who is ill), make sure adequate protection is used to the extent possible. At this point, patient and caregiver need to be closer together, so use all the protection you can have: respirator / mask, protective gown / raincoat, protective glasses / face shield, gloves. Train the proper procedures for putting these on and taking them off, going through that in your head over and over again.

From now on in this text, we will assume that you’re the caregiver. Read ahead for signs that indicate Level 4. The purpose of care in Level 3 is also to monitor the patient more and more closely so as to catch early any signs that the patient urgently needs expert medical care. For instance: If the patient is not able to drink at least 2 liters of fluids per day, you should (kindly) insist. Dehydration is a medical condition, and without a daily minimum, you’re quickly in Level 4.

In most cases, however, the patient will improve after a few days or at most a week. Just stay with it. Once the patient gets a little better, care may be done by the patient him- or herself again. Don’t be in contact any more than you have to, minimise the risk of becoming infected wherever possible. Make sure the illness diary is kept until all symptoms are gone, and quarantine is kept up until the patient has been symptom-free for 14 days. If you have been caring for the patient, self-isolate again. Your own two-week self-quarantine period now begins.

Care work

A large part of the work you are doing at this stage is care work, which may overlap with nursing but does not require specialized training. Remember that people who need help with basic self-care due to illness may be embarrassed to ask for or accept it. Be gracious. Everyone needs help sometimes. Think how to make the patient physically, mentally, and emotionally more comfortable and well; you might do this by asking yourself what you would need in their position, by watching for cues that may indicate discomfort (e.g., shivering, sweating), or by asking how you can help.

Some possibly useful behaviors include:

- Getting at eye level and at a distance that is large enough for comfort but small enough that they do not have to strain speaking loudly to talk to you. At the same time, try to put some distance between you and the patient where possible to prevent infection.

- Simple encouragement to drink and eat. E.g., “Drink, honey.”

- If the patient is not drinking or eating adequately, offer alternatives. E.g., if solid food is unappealing, what about soup, bouillon, or electrolyte solution? If hot drinks are unappealing, what about something cold, or vice-versa? If the patient can’t feed himself / herself, could you spoon-feed him / her?

- Checking that the patient is warm enough in the extremities (e.g., cold feet?) and at night.

- Setting up a fan to blow air in the patient’s face can relax patients who are feeling breathless. Helping the patient breathe in a fresh breeze from an open window if possible can have the same effect.

- Reassure the patient that it is very likely that he or she will make a full recovery (which is true). Offer relaxation techniques (calming music, humor, counting breaths).

- If breathing is labored, try breathing techniques (e.g., pursed lips or diaphragmatic breathing techniques) and positional changes. Positional changes include:

- Leaning the chest forward a little or putting the arms and head down on a table while sitting with feet flat on the floor.

- Sleeping on one side with a pillow between the knees. Or, sleeping on the back, elevating the head with a pillow or two. It is similarly a good idea to elevate the head of the bed for sleeping if possible.

- Lying prone – flat on stomach with chest down and back up – often raises blood oxygen levels in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). But it’s usually uncomfortable and not for infants or pregnant people. Also make sure there’s no fluffy pillow, mattress topping or blanket that can (partially) block air flow.

- Keeping the illness diary (see below).

Illness diary

As mentioned in the previous section, you might want to use this printable form, or make your own.

At this stage, measure the vital signs often, log them in the illness diary, and watch out especially for and note symptoms that might suggest worsening. Read the next section for more detail, but these include dizziness or rapid heart rate (drink more and eat something if you can), rapid breathing (elevate head while lying down or lower it to the table while sitting up for easier breathing), and a blue tint to fingertips or lips (cyanosis – get fresh air, get warm, and check blood oxygenation if possible).

If you think the patient’s condition might be worsening, your illness diary might expand to include the following:

- more frequent temperature readings

- respiration rate (breaths per minute)

- heart rate

- onset of new confusion (if the person seems to have less mental capacity than normal)

If the patient’s condition seems to be worsening, skip to the next section.

Go bag

If your condition deteriorates to the point that you / the patient needs to go to hospital, you will not have time or be in the mood to think about what to pack. So prepare beforehand a small bag with a zipper / firm closure that contains:

- A piece of paper with, in clearly readable print:

- Identifying information: Name, date of birth, address

- Names, addresses, and telephone numbers of loved ones and next of kin

- ( optional: pincode to patient’s cell phone )

- A list of any essential medications you are taking (drug, time, dose)

- A brief medical history, listing chronic health conditions and name(s) of doctor(s)

- A week’s supply of your essential medication, if applicable

- Government-issued ID, or a copy of that

- Health-ID card, health insurance card, whatever is applicable where you are

- A set or two of simple and compact fresh clothes

- Bath slippers (also known as flip-flops)

- Spare glasses if available

- Toothbrush, toothpaste

- Patient’s living will document, if applicable

- Phone charger if you have an extra

- USB battery pack if you have one

- Previous days of the patient illness diary

It would be ideal to have name and date of birth readable on the outside of the bag as well.

When it is time to go, remember to put glasses, phone, charger, and today’s page of the illness diary in the bag before you go. Remember that there will likely be no visits allowed in hospitals during peak pandemic phases, and COVID-19 patients (and others) may be in far-away makeshift hospitals or quarantine facilities staffed with medical professionals. We put your own essential prescription medicines on the list, although they are generally provided for you by the hospital when you are in the hospital. It’s just not always clear where you may be taken, or what level of care they will be able to provide, during peak pandemic times when the hospital system is likely to be overwhelmed. You may also want to download the free Patient Communicator app that could help you communicate in a hospital setting, even if you need to be intubated and therefore can’t speak.

Level 4 – Professionals Take Over

As symptoms get worse and the patient deteriorates, the frequency with which measurements are taken should increase. At this point, your log should contain temperature, respiration, and heart rate every few hours. Be especially alert for rapidly worsening shortness of breath, rapid breathing, and low blood oxygen level, as these can be signs of developing acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which requires immediate medical attention.

You should interpret any of the following as a medical emergency:

Loss of consciousness

There’s different levels. When patient loses consciousness, make a note of whether the patient responds when you call their name (Voice), when you pinch the shoulder forcefully (Pain) or whether he/she does not respond at all (Unresponsive)

If loss of consciousness is brief, you might (if patient quickly recovers and is fully awake again!) encourage the patient to eat and drink a bit, and freshly ventilate the room. But loss of consciousness is serious; get help.

Cognitive problems / confusion

You probably know the patient, so you should be able to tell without any fancy tests if and when he/she is not with it anymore. Sudden onset of confusion is trouble. Seek medical help.

Too high or too low respiration rate / shortness of breath

Count respirations per minute by holding your hand close enough to feel the patient’s breath, watching his or her chest, and / or watching his or her abdomen, while holding a clock with a second hand or a digital watch / phone stopwatch. Respiration rate (RR) should be between 12 and 20 breaths per minute.

Immediate home care for respiratory problems may include ventilating the patient’s room, and trying different breathing techniques and positions that can make breathing easier, too (see Level 3, Care work).

If you or the patient are experiencing shortness of breath / labored breathing, seek medical advice.

Low oxygen saturation

If you have an oxymeter (see shopping page), any oxygen saturation lower than 95% may indicate a respiratory problem. If at any stage the patient’s lips or fingertips turn blue (or even mildly blue; called cyanosis), call an ambulance! Anything less than 96%, get fresh air into the patient’s room, get him or her warm, and have him or her lie prone (chest down, back up) if he or she can.

(Also call a doctor if the fingers, toes, or lips turn less blue than this…)

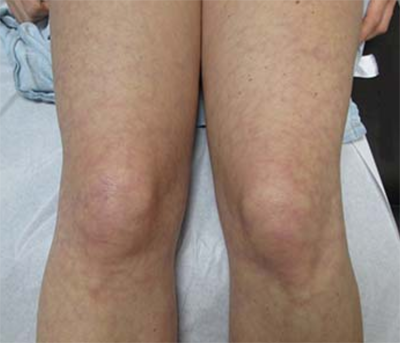

If the patient’s skin gets a lacy purple overlay (also called livedo reticularis) like below (and that’s not normal for the patient), that is also a reason to call for help.

Very low blood pressure

Blood pressure lower than the bottom of the normal range (90 mmHg systolic, 60 mmHg diastolic) is cause for concern. Note that blood pressure comes as two numbers, the systolic and diastolic pressure. If you have a cheap automatic device it should tell you both these numbers. If you have a device, note the systolic pressure on the diary form.

If you do not have a device to measure blood pressure or have trouble getting a reading, then try testing the patient’s capillary refill time instead. Check by placing his or her fingers flat on a hard surface. Use your finger to press down on one of his or her fingernails from the top. The fingernail should lose color. Check how long it takes the fingernail to turn its normal color again. It should take 1-2 seconds. Longer than that may indicate low blood pressure.

Dehydration is a common cause of low blood pressure, so immediate home care may include encouraging the patient to eat and drink, especially foods or beverages containing essential electrolytes like potassium and sodium. Dizziness is a common symptom of low blood pressure, so the dizzy patient will want to be careful while changing positions (laying to sitting up, sitting to standing); fainting may occur. But really, once again, if things do not look right somehow – if blood pressure is very low, or if the patient normally has high blood pressure and it’s looking much lower than their normal – again, get help.

Too high or too low heart rate

Heart rate is easier to measure than blood pressure, and usually high heart rate (above 100-110 beats per minute for an adult) goes with low blood pressure. Smaller adults and children often have normally higher heart rates. High heart rate alone may not be cause for alarm, as it may indicate anxiety or dehydration. Relaxation techniques and drinking / eating something might be appropriate. But once again, values outside the normal range here should cue you to seek medical help immediately. This is especially true if you see rapid breathing along with low blood pressure, high heart rate, and / or confusion.

Very high fever that comes (back) suddenly

If you check temperatures regularly, you will want to be aware that the trend can reverse suddenly, even when the patient seemed to be doing better earlier. Regular measurements are important. A fever that is very high (39.4° Celsius or around 103° Fahrenheit, or higher) is a cue to seek medical advice. So is a fever that goes away and then comes back suddenly.

Coughing up blood

This one is self-explanatory. If you notice the patient coughing up blood or blood-stained mucus, seek medical advice.

Call for help

When any of the above symptoms occur, things are serious! If at all possible, this is the point where you should not be taking any decisions based on a guide from the internet anymore. Do not wait for things to get worse. Call a doctor, or call the emergency number and get the patient in an ambulance pronto. Stay calm and report the situation as it is. Your job is done: You have kept a patient out of the medical system while he or she was just sick. Now it’s time for professionals to handle it. The data you have been gathering should hopefully help you convince the operator, paramedics / emergency medical technicians, and doctors that you are not merely panicking for no reason, and will likely help get the patient the care he or she needs sooner.

Level 5 – System Overload

What if the official channels are overloaded?

What we’re unfortunately seeing in some areas is that the system becomes stressed to a breaking point if too many people become sick at the same time. Either you cannot get through, you are told the ambulance is going to take a while, hospitals are not taking new patients at all, or some hospitals prioritize treatment of certain groups of patients (such as the relatively young and healthy) over other groups (such as the elderly and / or people with existing illnesses).

In the event that official means of getting medical help are unavailable, you might want to try to get hold of that doctor you know, the nurse down the street, anyone with medical training and / or experience. If that doesn’t work, depending on the urgency, you might want to mobilize your and the patient’s wider circle. Let people around you know that you have a patient who is not doing well and that you cannot get help. Ask around for doctors or nurses. For example, you might try using Facebook, a grocery store bulletin board, or any other social networking tool or technology that makes sense to you. If you have any spare time after that, organize your diary pages, making sure any doctor who has time for the patient can immediately see temperature records, etc. Try not to seem too worried around the patient, because at this point there likely isn’t anything he or she is going to be able to do.

If you do get through (by phone?), try to stay calm and help the doctor / hospital assess the situation quickly.

In cases where ambulances are the bottleneck and you feel you need one, you will have to make your own judgement whether you want to try and drive to the emergency room, or wait and hope to get through. Plan which hospital you will go to before leaving, and maybe include someone who is not driving who has access to the internet to help navigate – either in the car or on the speakerphone. Please drive safely in any case; the last thing you want is a sick patient in a car accident.

For now let’s all hope our medical professionals can cope with the case load that is coming to them. Do your part in slowing the disease down as much as possible. Let’s try to all still be there at the other end of this.